-

Company

-

Brands

- A House of Brands

-

Hearing Instruments

-

Consumer HearingConsumer Hearing

-

Cochlear ImplantsCochlear Implants

-

Audiological CareAudiological Care

- AudioNova - Brazil

- AudioNova - Denmark

- AudioNova - Italy

- AudioNova - Sweden

- Audition Santé - France

- Boots Hearingcare - UK & Ireland

- Connect Hearing - Australia

- Connect Hearing - Canada

- AudioNova US

- Geers - Germany

- Geers - Hungary

- Geers - Poland

- Hansaton - Austria

- Lapperre - Belgium

- Schoonenberg - Netherlands

- Triton Hearing - New Zealand

-

Investors

- Investors overview

- Ad hoc announcements

- Why invest in Sonova & strategy

- Presentations & webcasts

-

Financial reports

- Current outlook

- Key figures

- Financial calendar

-

Corporate governance

-

Sonova shares & bondsSonova shares & bonds

- General Shareholder's Meeting

- Services & contacts

- Newsroom

-

Careers

-

Your career with us

-

Apply now

-

Why Sonova

- Get to know our talents

-

sonova global

- Global

-

North America

North America

-

Pacific

Pacific

-

Latin America

Latin America

- Asia

- Europe

Global

North America

Pacific

Latin America

Asia

Europe

-

Company

-

Brands

Brands

- A House of Brands

- Hearing Instruments

- Consumer Hearing

- Cochlear Implants

-

Audiological Care

- AudioNova - Brazil

- AudioNova - Denmark

- AudioNova - Italy

- AudioNova - Sweden

- Audition Santé - France

- Boots Hearingcare - UK & Ireland

- Connect Hearing - Australia

- Connect Hearing - Canada

- AudioNova US

- Geers - Germany

- Geers - Hungary

- Geers - Poland

- Hansaton - Austria

- Lapperre - Belgium

- Schoonenberg - Netherlands

- Triton Hearing - New Zealand

-

Investors

Investors & financials

- Investors overview

- Ad hoc announcements

- Why invest in Sonova & strategy

- Presentations & webcasts

- Financial reports

- Current outlook

- Key figures

- Financial calendar

- Corporate governance

- Sonova shares & bonds

- General Shareholder's Meeting

- Services & contacts

- Newsroom

- Careers

sonova global

Choose your country

- Global

-

North America

North America

-

Pacific

Pacific

-

Latin America

Latin America

- Asia

- Europe

Global

North America

Pacific

Latin America

Asia

Europe

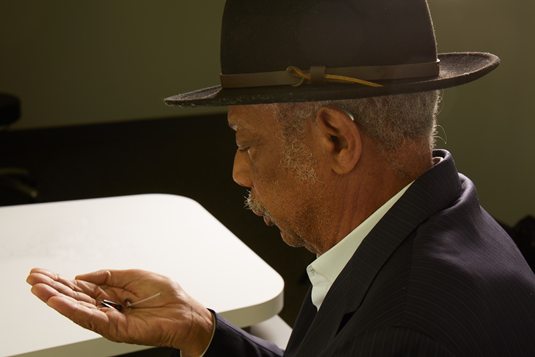

“It’s like having new ears!”

Charles Owens is a jazz musician – and he wears hearing aids from Sonova brand Phonak. The saxophone player, who is over 80, finds them crucial, not only for listening to music and communicating with the members of his band, but also to help him teach his students and stay fully focused when his nine-year old grandson practices saxophone with him.

“Whereʼs Glo?” Clad in a black suit, white shirt, red tie and matching fedora, Charles Owens strolls through the back door of the Lighthouse Café in December 2019. In one hand, he is carrying his saxophone case and, in the other, a bouquet of roses for Gloria Cadena, who is over 90 and decides which jazz bands get to play in the club.

Itʼs time to open the doors for the jazz brunch that has been a weekend tradition since 1949 in the club, a few miles south of Los Angeles, whose global fame was kickstarted by the film La La Land. Charles gathers his band to discuss the bebop classics he wants to play that morning. “The important thing with jazz is to play with enthusiasm,” he says, surveying the packed room with satisfaction. He can hardly wait to take the stage, raise the tenor sax to his lips, and entertain the public. For Charles and the saxophone, it was love at first sight.

It all started back in 1949: Ten-year-old Charles and his parents are on their way from San Diego to Oklahoma to visit his fatherʼs family. “They were all musical,” he recalls. Charles discovers every instrument imaginable in the sitting room – guitar, drums, trumpet, trombone, and a silver-plated alto saxophone. He tries them all out, but is particularly taken with the sax. “When we got back home, I asked my mother if I could have it,” he recounts. “She bought it from Uncle Henry and had it shipped to California.” Seeing his enthusiasm for the instrument, his parents sign him up for lessons.

At high school, Charles starts a band with some friends and they play at parties on weekends. The money he makes goes towards music, books, and shoes. His dream is to master the saxophone as well as emulate the great jazz musicians. When a teacher asks him just before graduation what he intends to study at university, thereʼs only one possible choice: music.

“Jazz is your vocation – you have to practice!”

And he does it, too, playing in the brass band in college and earning money on the side in a fast food restaurant. “My burgers were good, but I knew that wasnʼt the life for me,” he recalls. Charles signs up for the military and joins the Air Force Band, which takes him to Boston and the Berklee College of Music to study jazz. There, he switches from alto to tenor sax and learns piano, trombone, flute and clarinet. In Boston, he begins his career as one of the most multi-talented jazz musicians there is ever likely to have been. His sheer versatility enables him to work with the worldʼs top musicians.

Shortly after his 32nd birthday in 1971, he heads for the bright lights and big city of the West Coast to buy a house for himself and his family. With financial support from his wife, Charles plays in jazz clubs, but feels guilty as he is no longer earning any money. His mother constantly pushes him to find a part-time job instead of spending hours perfecting his technique. “Let them talk,” Duke Ellington eventually tells him while he is touring with his orchestra. “Jazz is your vocation – you have to practice!”

His discipline and patience begin to pay off and Charles is soon a sought-after session musician. “Itʼs a blessing when you find out what God put you on earth to do,” he says emphatically. “Itʼs even better when you can do it your whole life and it pays the bills.”

In 2015, a call comes through from Hollywood. “They said, ʼtheyʼre making a film in the Lighthouse Café, come down and bring your saxʼ.” By this point, Charles and his band have been playing regularly at the club for more than 20 years. The film, which will see him taking the stage behind Ryan Gosling, Emma Stone and John Legend, is called La La Land. To Charlesʼ delight, it will bring jazz to a whole new audience and entice the curious into the Lighthouse Café.

Before the premiere in December 2016, Charles and his band would sometimes play to only a handful of brunch-time regulars. This all changed after the film, with fans jostling in queues round the block for hours before the doors open each weekend. All the tables are booked out this Saturday morning as well.

“Everything was distorted and crackly”

“Am I glad that youʼre all here,” says Charles when greeting his guests. “Itʼs depressing to play with no audience – itʼs enough having to do that every day at home!” Before the laughter has even died away, the first rich notes from his saxophone are floating through the air as tourists look up from their smartphones and tap their feet to the beat.

After the first set, Charles introduces the members of his band and points across to the Sonova team standing beside the stage with their cameras and spotlights; they are making a short film about him. “The moviemakers are in today, as you can see,” he says. “Itʼs not ʼLa La Land IIʼ – they are filming me because I wear a hearing aid.” He takes a short pause, wishing to make sure that everyone is paying attention to him. “Something a lot of you donʼt know – Iʼm half deaf. Not exactly ideal for a musician!”

Charles had noticed his hearing loss not on stage but at home. His familyʼs complaints that he was turning up the television too loud were becoming more and more frequent. When they turned the volume down, he could no longer hear anything, and he was finding it harder and harder to conduct a conversation. “I had got used to asking what someone had just said and always getting them to repeat it,” remembers Charles. He thinks his ears have suffered because he always likes to stand right next to the percussion. “The drums could never be loud enough for me.” For a long time, he was too proud to get a hearing aid and was embarrassed about admitting to his hearing loss. However, once sitting in front of the television with his family became no fun anymore and communicating with them was becoming increasingly difficult, he acquired his first hearing aid. It was a lot better than having no help at all, but there were still some problems – on the phone, for example. “Everything was distorted and crackly.”

Things changed radically when he acquired his Phonak hearing aids. “Itʼs like having new ears! As if Iʼd been underwater before and have finally come up to the surface,” says Charles enthusiastically. “These are really first-class hearing aids.” When his phone rings, all he has to do is press a button on the device and he is directly connected, and can hear the voice at the other end clearly and distinctly. “Now, I can hear the rain on the roof again, the birds singing, and the pastor at church. Previously, it took a lot of effort to discuss song arrangements with his bandmates, catch what a taxi driver was saying, or understand what fans were asking him. Now, he finds all this easy again and it is also a lot more fun to listen to his nine-year-old grandson practicing his saxophone with him. “You canʼt put a price on that, and there isnʼt a note I would want to miss. Now, I can finally hear them all again.”

The hearing aids also make his work easier with students at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He teaches saxophone there once a week – a job that brings him tremendous satisfaction. “I want to pass on what I have learned,” explains Charles. “And more than ever before, I want jazz to reach as many people as possible so they can forget their troubles for a moment as they listen.”

“And more than ever before, I want jazz to reach as many people as possible so they can forget their troubles for a moment as they listen.”

In 2010, Charles released an album of original compositions and cover tunes. It was entitled Joy, a synonym for his attitude to life and to jazz. “I will play music until the last drop of energy in my hearing aid batteries drains to nothing,” he says with a laugh, and lifts up his sax again. Itʼs time to entertain his audience and spread joy.

In December 2020, Charles is fitted with the Phonak Audéo™ Paradise hearing aids. These multi-functional devices deliver improved hearing performance and speech understanding1, coupled with industry-leading wireless connectivity. To try them out for the first time, Charles has come to the Sonova brand Connect Hearingʼs audiological store. Both the jazz musician and the audiologist have to wear masks for the occasion. Coronavirus is spreading in Los Angeles as well, so safety precautions are strictly observed during the fitting.

“This fitting makes me feel like an artist,” says Ivan Wu, Senior Regional Director for Connect Hearing. His creative challenge is to reproduce the sounds of the world in as much varied detail as possible in the ears of his client, and to translate the musicianʼs wishes into commands for the computer program.

Charles is excited. “Itʼs like having a top-of-the-range car and upgrading to the latest model – adding the little details is always the cherry on the cake.” With Phonakʼs Paradise devices, these include a motion sensor that adjusts the hearing aids automatically when Charles is sitting still, playing saxophone or going for a stroll with his wife, for example. “For a lot of our customers, we only have to dial in two or three settings,” comments Ivan Wu. “With Charles, we have a whole gamut of possible voices and background noises to consider.”

Charles hears one little difference straight away. “Voices are even crisper, despite the masks!” But he adds that the acid test will come only when he is able to play in front of a live audience in a club again. Charles is confident that this will soon be possible. He can hardly wait.

1 Appleton, J., & Voss S.C., (2020) Motion-based beamformer steering leads to better speech understanding and overall listening experience. Phonak Field Study News in preparation. Expected end of 2020; Wright, A. (2020). Adaptive Phonak Digital 2.0: Next-level fitting formula with adaptive compression for reduced listening effort. Phonak Field Study News, retrieved from www.phonakpro.com/evidence, accessed August 19th 2020.